|

|

iMahal Interview Series:

iMahal Interview Series:

David Gimbel

July 22, 2001

iMahal:

English literature was something you loved, so you pursued it. That makes sense. But you jumped to a different path in graduate school. How did that come about?

Gimbel:

When I got out of college, I had never conceived that I would end up in a graduate program. In fact, I had never functioned particularly well within the confines of the school system. I got fairly good grades, but I was not really happy with a system that was constantly telling me what to do.

I graduated in 1989. At that time the country was still in a recession. It remained that way for a few years. It was difficult to find a job. I got an internship, as an editorial assistant at a literary journal called the Paris Review, which is here in New York. It's a long-standing academic journal, and I worked there for a year, primarily reading manuscripts.

Gimbel:

When I got out of college, I had never conceived that I would end up in a graduate program. In fact, I had never functioned particularly well within the confines of the school system. I got fairly good grades, but I was not really happy with a system that was constantly telling me what to do.

I graduated in 1989. At that time the country was still in a recession. It remained that way for a few years. It was difficult to find a job. I got an internship, as an editorial assistant at a literary journal called the Paris Review, which is here in New York. It's a long-standing academic journal, and I worked there for a year, primarily reading manuscripts.

Then I needed to make some money, so I worked for a while as a paralegal. And I worked at a bunch of other jobs. I was miserable. I was in a black hole. I hated what I did every single day. I was worried that the rest of my life was going to be the same thing over and over again: working simply to get money to feed myself, so that I could wake up, work again to get money to feed myself, so I could go to sleep again and then wake up again and then go to work again...

At about that time I had a little bit of money and I sat down, very depressed, and asked myself a very important question, "What do you really enjoy doing?" I realized that I was spending most of my time either in museums or reading about history, or reading about linguistics. And I thought, well, maybe there is some way that at least now that I have enough money to float myself for a semester I could go back and take some courses in some of the subjects that interested me.

I was fortunate in that I had read a couple of books by people that I liked and who I thought were talented thinkers. Two of them happened to be at Columbia University. One was a woman named Esther Pasztory who wrote primarily about Aztec art. The other was a woman, very old at the time, named Edith Porada who studied ancient Near-Eastern art. I was able to get myself into a class with each of them at Columbia through the School of General Studies, which was a fantastic program because you didn't have to be enrolled in Columbia and you could still take these fantastic courses. As I got more and more interested I applied to a variety of art history programs.

I ended up being accepted at Columbia. At that time, although my real passion was Near-Eastern history, particularly Elamite, Sumerian, and Akkadian, I had no intention of studying the ancient Near-Eastern cultures for one simple reason: I didn't want to learn the languages. Already my Spanish was fluent, my French was pretty good, and I thought, well I'll do pre-Columbian because I already have the skill set to be able to go into this. But an odd thing happened to change my mind. One day I was sitting at the back of this tiny seminar in the basement of the Morgan Library taught by this old Viennese professor Edith Porada, and there was a slide that was mistakenly mixed in with the rest of the slides. The slide popped up on the screen and Professor Porada said, "Oh, well that shouldn't be there. But by the way, does anyone know what that is?"

And I looked at it and said, "Yeah, that's spouted ware from Hassanlu level IV, or Sialk B," which was a completely different topic than what we were studying and she paused, looking at me at the back of the class and then asked, "Who are you? And what are you doing here?" I was really embarrassed. I said, "Well, my name is David Gimbel and I'm sitting here because I'm kind of interested in what you're teaching." And she said, "No, it's more than that. Why are you here?" And I continued to kind of stutter and trip all over myself. And she said, "Well, we'll have to discuss this later." So I kind of wiped the sweat off my brow, thinking, this is a relief, I don't have to explain myself.

I went home and that night I got a call. I picked up the phone, and this great professor said to me, "Mr. Gimbel, what do you intend to do with your life?" I thought this was a very peculiar way to start a phone conversation.

|

..Mr. Gimbel, what do you intend to do with your life?..

|

And I said, "Well, I don't really know, I'm kind of trying to think this through, and I've applied to a bunch of art history programs including Columbia." She said to me, "Mr. Gimbel, you are an idiot," and hung up the phone. So I thought, well I must really be in deep trouble now.

The next day I woke up and the phone rings, and it's professor Porada again.

|

..Mr. Gimbel, you are an idiot..

|

She says to me, "Mr. Gimbel you might wonder why I called you an idiot." I admitted that this was something I had been thinking about. And she said, "You are an idiot because you have applied to the art history program at Columbia and you have not asked me for my help, and now it is too late to help you."

I thought that this was also kind of peculiar. I didn't really want anybody's help. In fact what I really wanted was not to have anybody's help, and make it on my own merits. A couple days passed and then I got another call from her, and she said to me, "I assume that if you are admitted to this program, you will come and study Near-Eastern history."

|

..That's utter nonsense..

|

And I said, "I'm terribly sorry, but that is an incorrect assumption. I have no intention of studying that. If I get in I'm going to study pre-Columbian." And she said to me, "That's utter nonsense. This is what you love; this is what you should do." About a week or two later I found out that I had been admitted into the program. She asked me to meet her at the Morgan Library so I went there and met with her. She was very frugal. She had a sandwich prepared for me, and a cookie. We sat down and she said, "I have something for you." She brought out this stack of papers and said, "I have visited the Austrian embassy and I have asked them to give me information about all of the various language programs in Austria. Once you are admitted you are to come to Austria and you are to study German and then after you are done with your German you are to come stay with me for the next 3 or 4 weeks in Haggengut," which was her family home in the mountains outside Vienna.

|

|

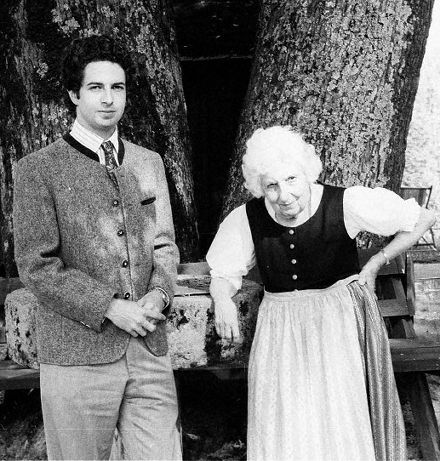

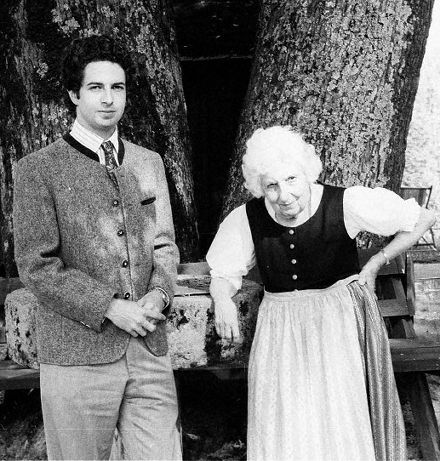

David Gimbel with Edith Porada in Haggengut

|

I ended up studying German in Salzburg that summer and then went to Haggengut to visit her and her sister. Each morning she would assign me a German article to translate into English.

|

..She still gives me a lot of homework..

|

I remember a lot of them seemed to be about ancient metallurgy, I have no idea why. She would then review my translation after lunch. Her first student, Professor Maurits van Loon, was also staying there with his wife. He was retiring that year. I remember watching him walk up the stairs one evening with a pile of books and offprints. He looked down at me and sighed, "She still gives me a lot of homework."

All photographs copyright and courtesy of David Gimbel or Archaeos

|

|